The Difficulties of Grade Inflation

Over the past century, average grades have been rising. This process, called grade inflation, is when the average grade trends upward, so students in general are earning higher grades than they would have 50 or 100 years ago. Grade inflation is generally more severe in elite high schools and colleges; the median grade at Harvard is an A-minus, and grades are not even given at Yale Law School. This is surely an issue for which changes can and should be made; however, the different sides of the issue clash on whether grades should be deflated, or if grades should be replaced with other means of evaluation.

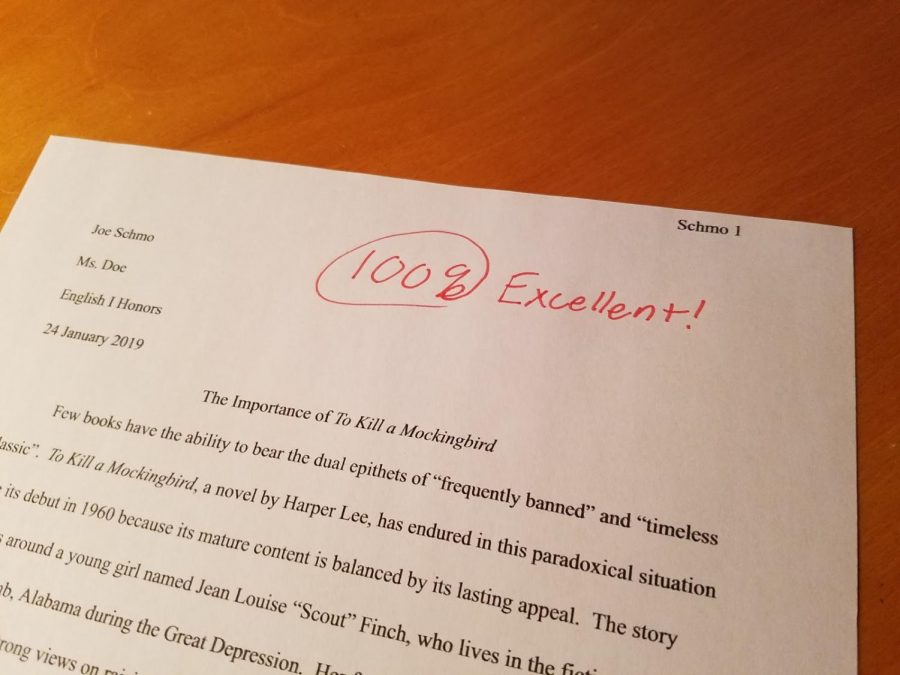

Those who want to deflate grades argue that this approach will solve the problems associated with inflated grades. One fundamental issue is that the inflation reduces the value of the grade as a tool for comparison. For instance, college admissions officers may have trouble determining which students are above average when most earn high marks. Will Walters, a student at Cherokee, raises another valid point: “Grade inflation is a negative thing because it disregards the grading system so that there is no real way to compare your success to the actual grades that you are earning.” If individuals earn high grades in all of their subjects, they won’t be able to tell what they excel at and where they struggle.

However, deflating grades back to their original levels is not the only, nor may it be the best, solution. In 2004, Princeton enacted a policy stating that the average number of A grades per department should not exceed 35%, but it failed a few years later as the students continued to perform well despite the policy change. Furthermore, the grading system itself is flawed in that it necessitates competition between students to best their peers in order to be considered successful. The most promising alternative to traditional grades is a written summary of student performance by the teachers, like an honest letter of recommendation. A candid description of the student with his or hers strengths and weaknesses would be far more valuable to colleges and employers than a list of letter grades that purport to sum up that student’s entire experience in that class.

Descriptive evaluations of students are superior to letter grades because they serve as a more complete picture of the student as a person. Regular transcripts can only provide information about a student’s aptitude for taking tests or writing papers, while a written overview of that same student would be able to provide feedback and explore areas not covered by an averaged set of scores. For example, students’ participation in class and level of commitment to their education are vital factors that are often overlooked in the grading process; therefore, showing colleges and employers that someone excels as a human being in addition to as a student is invaluable. No matter how grades evolve in the future, this alternative method will allow educators and employers to confidently select the young adults that will best fill their positions.