Dear Anne Frank

“I don’t want to have lived in vain like most people. I want to be useful or bring enjoyment to all people, even those I’ve never met. I want to go on living even after my death!”

✧✧✧

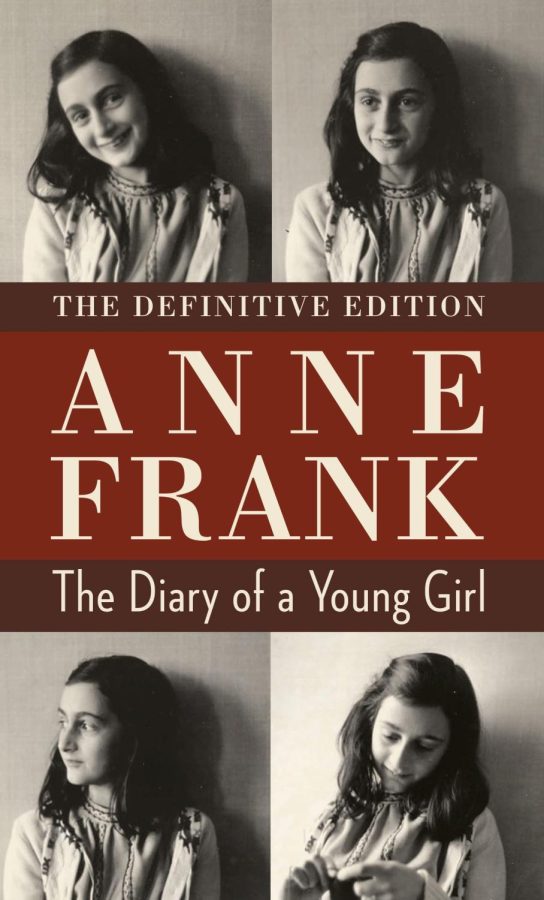

I heard Anne Frank’s name as a child, long before I read her diary. I used to think, what extraordinary work did this young girl write to be remembered so many years after her death? How outstanding of a person might she have been to have created such a profound lasting legacy before she even turned sixteen?

Here’s what I knew beforehand: Anne Frank was a Jewish girl that lived during the Holocaust. Her family hid in a safe house where she wrote in her diary, eventually dying young. Of course, all those things are true, but it took me just one turn of the page to realize her story was so much more complex than I had imagined it would be.

It was Anne’s thirteenth birthday when she received the diary as a gift. She decided to address the diary by the name of “Kitty,” and wrote on the first page, “I hope I will be able to confide everything to you, as I have never been able to confide in anyone, and I hope you will be a great source of comfort and support.” Intrigued, I turned page after page, thoroughly captivated by Anne’s gorgeous, fine spirit. She burns so brightly it is almost blinding, with youth, hope, and optimism. Even as her confinement darkened as the years went by, she remained hopeful to one day be free, to be full, and to be a good person.

What is undeniably striking about Anne’s diary is her vivid and articulate storytelling. Reading through it, I felt like a ghost floating about the safehouse, witnessing every dinner, every prayer, every teardrop, and every smile. A voyeuristic type of guilt crept on me as Anne wrote about her parents, independence, identity, depression, love, faith, and hope, with such sacred confidence in her diary. Writing it, she had never expected that millions of readers would one day step into the role of her “darling Kitty,” hanging onto every word she had written so passionately with admiration. Despite living a life worlds away from hers, I feel an indescribable connection with Anne. I feel that I’m living the life she would have dreamed for herself and that I must make use of it, in a way, to do her justice.

A quote I feel best captures the essence of Anne’s outlook is this, “In spite of everything I still believe that people are really good at heart. I simply can’t build up my hopes on a foundation consisting of confusion, misery, and death. I see the world gradually being turned into a wilderness, I hear the ever approaching thunder, which will destroy us too, I can feel the sufferings of millions and yet, if I look up into the heavens, I think that it will all come right, that this cruelty too will end, and that peace and tranquility will return again.” Her optimism is simultaneously beautiful and endlessly heartbreaking, knowing how she died so young. It is my belief that Anne’s strength and gentleness didn’t save her life, it transformed the world as well as humanity’s recovery from the tragic war.

Needless to say, Anne’s diary is not a great work of philosophy. It is simply her emotions and observations, expressed rawly and without restraint, as she lived through one of the most horrendous events in history. She wrote about growing up fast and being misunderstood. She wrote angrily about her parents and lovingly over her crush. She wrote optimistically about the future despite the war. Of course, Anne did not live during any ordinary time, but these feelings she expresses are universal—and that’s what makes her diary so extraordinary. It is not Anne in particular who is the outlier, the “special” one, but the articulation of her rich inner life that makes us all aware of our own extraordinariness.

But Anne, I wish I could speak to you in the flesh. I wish I could take you by the hands and look into your eyes and be a truer friend to you. I imagine us lying in the fields in the spring, the sun shining over us graciously, the birds’ song, the scent of grass and tulips in the breeze. I would gush over your writing. I would tell you I understand everything. We could be angry at our parents and the world together, and you could tell me about Peter and I’d roll my eyes and say he’s not worth the trouble.

I believe in goodness and happiness as you do, and I hope to live on past my death just as you have. I wish that I could tell you, that you could know how it has ended—that it hasn’t ended. But alas, you will never read this. You would’ve been seventy-seven today. Thank you, Anne.

Your friend,

Kitty