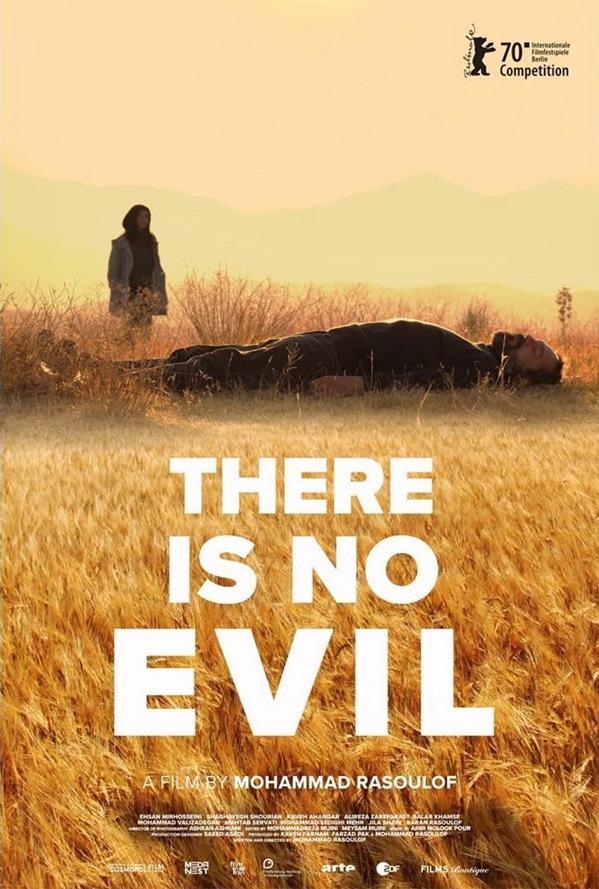

“There Is No Evil”: A Chilling Look at Capital Punishment in Iran

Iran is one of the few countries in the world that still gives out the death penalty and it carries out many executions. Iran also has some of the strictest rules regarding filmmaking. However, this has not stopped Iranian filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof from directing what is viewed as one of the most important feature narratives of the year. Rasoulof’s previous films have already obtained him a year’s imprisonment and a temporary filmmaking ban. Rasoulof has yet to turn himself in because of COVID-19. He has created a work that criticizes Iran’s use of capital punishment with four distinct, enthralling, and thoughtful vignettes.

The first vignette, “There Is No Evil” (which translates more directly to “The Devil Doesn’t Exist”), follows a modern-day middle-aged Persian man for the film’s first half-hour. We see him drive out of a heavily guarded building, pick up his wife from work and his daughter from school, attempt to get money from the bank, arrive at his mother-in-law’s to take care of her, and eat pizza. Then he wakes up in the middle of the night to drive to that guarded building and begins his day’s work. The section ends with one of the most haunting, effective, and brilliant choices of editing in recent memory, which sets the tone for the following three stories.

Throughout the next two hours, we see the effects of Iran’s execution process on different demographics. In “She Said, ‘You Can Do It,’” a young man serving his mandatory army time in prison attempts to find any way to avoid performing his first execution. After lots of interesting expositional dialogue, the section takes an exciting turn. In “Birthday,” another man on break from his army duty returns to his to-be-fiancée’s house during a party only to learn that his job and her family’s life have crossed paths horrifically. Lastly, in “Kiss Me,” a teenage girl from Germany travels to her uncle’s house for vacation and learns a long-hidden, harrowing secret in what is a slow-burning plot. Each vignette involves capital punishment in a unique way and as they go on they only further cement the main ideas about the fatal flaws of executions in Iran into the viewer’s mind.

The strongest part of “There Is No Evil” is its script. If the four vignettes were released as separate short films, they would each be fine works on their own. But together, in the order that they are, they become one whole, haunting figure. While each of them is paced differently (they are all slow, but each moves along in its own way to its conclusion), they all work to convey the unilateral theme and use their slow introductions to drag the viewer into their shocking moments of realization. The Iranian government has called Rasoulof’s films “propaganda against the government,” which clearly wouldn’t happen in our free-speech-guaranteed nation. One cannot deny that “There Is No Evil” serves a purpose to convince its viewers of something political — that Iran’s capital punishment is detrimental to the lives of citizens. My only criticism here is that at times the vignettes can slightly drag on and “Kiss Me” is a bit too predictable in comparison to the preceding three. But even then this does not alter the film’s effectiveness or clarity.

It is not just the screenplay that gets the point across in this film. Practically every aspect of “There Is No Evil” works to communicate the inevitable message Rasoulof wants us to hear. The actors, with their meaningful dialogue and thought-provoking expressions; the production design showing a microcosm of Iran’s locations and culture, from the winding halls of a prison to the serene view of isolated homes; the stagnant cinematography, gazing on the action (or lack thereof) of the four vignettes, and showing no bias or sentimentality towards the more meaningful moments; the aforementioned editing which gives the viewer the first taste of the ensuing darkness; and Rasoulof’s direction, which shows no mercy at all, all work together to create a mesmerizing and complete work.

There is no doubt why “There Is No Evil” has won several festival awards already, including the prestigious Golden Bear at last January’s Berlin Film Festival. Not only is it effective, beautiful, and energizing, but it is incredibly important because of how the film conveys messages to its viewers and also provides the history of post-revolution Iran. There are already a few recent Iranian films that have been revered and remembered worldwide such as “Close-Up,” “Taste of Cherry,” and “A Separation”; “There Is No Evil” is sure to join their ranks.

4.5/5 Feathers